Operant conditioning relies on consequences—punishments and reinforcers—as a means of either decreasing or increasing a subject’s likelihood of repeating a behavior. Punishments decrease; reinforcers increase. Both come in positive and negative—either adding or removing something.

Operant conditioning relies on consequences—punishments and reinforcers—as a means of either decreasing or increasing a subject’s likelihood of repeating a behavior. Punishments decrease; reinforcers increase. Both come in positive and negative—either adding or removing something.

So:

- You steal my toy, and I punch you, so you’re less likely to steal it again. This is positive punishment.

- You steal my toy, and I stop talking to you, so you’re less likely to steal it again. This is negative punishment.

- You share your toy with me, and I share one of mine in return, so you’re more likely to share it again. This is positive reinforcement.

- You share your toy with me, and I stop whining for you to share it with me, so you’re more likely to share it again. This is negative reinforcement.

I have, you may be able to tell, been thinking a lot about motivation lately.

Here’s the thing. Fear is a powerful motivator. Fear—justified and otherwise—is a driving force in society. Fear is a useful adaptation—it helps us survive. Fear says, “Don’t mess with that lion. It could probably maul you.”

Fear is a product of punishment—either directly or by proxy. I can take a lesson from seeing what happens to a zebra who gets too close to that lion. Fear pushes us to avoid bad things, and that’s a healthy quality.

But fear isn’t enough. Fear may prevent mauling, but it won’t promote greatness. That’s where reinforcers come in.

I see this a lot—in myself and my peers, in writing and work and relationships and life. Fears of failure, of judgment, of rejection—they drive us to seek safety. We write what is least risky. We stay by the trunk, way back from that limb, or maybe out of the tree altogether. All manner of beasts could be loitering up there.

I see this a lot—in myself and my peers, in writing and work and relationships and life. Fears of failure, of judgment, of rejection—they drive us to seek safety. We write what is least risky. We stay by the trunk, way back from that limb, or maybe out of the tree altogether. All manner of beasts could be loitering up there.

And because of this, we are not great. Fear motivates survival and not much else.

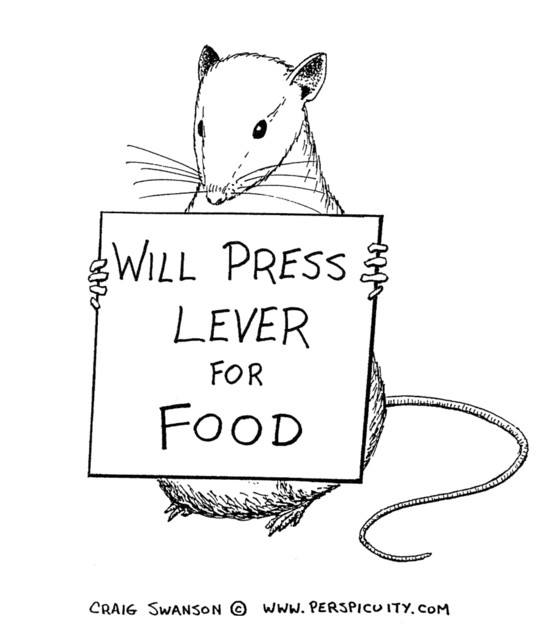

I’ve talked before about motivation through the lens of incentivizing preschoolers, so I’m going to take it back another level (and see how far I can go before being accused of condescending and over-simplifying). A common tenet of dog training is that “positive reinforcement is one of your most powerful tools.” By reinforcing rather than punishing, you show a dog what behaviors you want, rather than leaving him to figure it out by process of elimination. (I’ll let you come up with your own house training joke for that one.)

Punishment motivates fear. Reinforcement motivates desire.

For writers, rejection is in no short supply, even if we’re not submitting work for publication. We can apply to programs or workshops and receive the stock thanks-but-no-thanks that sometimes comes with a note of regret, mentioning the high number of applicants and the limited number of spaces and how many talented writers are being turned away, as if any of these things make the NO any less NO-like. We can share a piece with a reader whose opinion we trust and get a response that is lukewarm only out of consideration for our fragile egos. We can finish a draft and feel good, then return to it two weeks later and find it appalling. Even the most introverted of us are still human, and humans are social beings, and to a social being, rejection is one of the worst punishments out there. (Rejection by other humans, at least. There’s a certain relief in being turned down by the aforementioned lion.)

This, I think, is why it’s so vital for us to find writing intrinsically rewarding, so that it becomes a reinforcer on its own. For all our insecurities, writing requires a degree of arrogance, and it’s one we have to embrace. We have to believe that what we do has value, that when we tell ourselves, “Sit, writer!” and plop down at our desks, we’ll get a Milk Bone of positive reinforcement. Or, if Orwell is right, and “Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout with some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand,” then perhaps we’ll receive negative reinforcement in the form of some relief, however momentary, from that demon.

(Note: One could mistake this for positive punishment, in that the demon punishes a lack of writing, but operant conditioning deals with the consequences of actions, not inaction.)

Either way, if we work from a place of fear, we may survive—it’s not guaranteed, but it’s the best we can hope for; if we act from desire, we’re not guaranteed success, but at least we’ve got a chance at it.

Leave a Reply