When I was working with a professor to finalize my portfolio for grad school applications, she suggested I apply to read one of my pieces in the university’s Undergraduate Symposium in March. It was November at the time, and with my mind ensnared as it was in the application process, concepts like reading and Symposium and March seemed like abstractions, whereas something to list on your minimalist CV was all too real. I gave brief thought to the fact that I’m not very comfortable with that sort of thing, then submitted a proposal and went back to thinking about grad school.

January rolled around, and I got an email saying my proposal had been approved, but I was still too caught up hoping for other acceptances for it to really register. Then it got to be the weekend before the Symposium, and it suddenly occurred to me, in an uncomfortably real way, that I had to give a reading soon.

I get the sense I am not unique in my performance anxiety—after all, it combines the usual stress associated with sharing work with the stress of public speaking. I wouldn’t go so far as to call it a perfect storm, because there are always ways to make it worse, but it’s a pretty damn good storm. We’ll call it 8.5/10.

So what do we, as writers, do? The reading is a potentially powerful medium for sharing our work … but also potentially disastrous, if we, for instance, become so nervous that we vomit on the podium. I don’t think there’s a single formula for success, but the first step is often to stop fixating on the possible nauseous disasters. Beyond that, it breaks down to being aware of your weaknesses and then doing those things better (a strategy that applies to most areas of writing, and life in general, thanks to its vagueness).

It helps to have someone who can act as a coach, or at least a one-person audience that doesn’t mind listening to you read the same paragraph over and over. For me, this came in the form of a more performance-savvy writer friend, who pointed out some of my bad habits and gave me some advice on how to remedy them, along with words of encouragement. Accept those words—this goes along with not thinking about the disasters. Don’t try to undercut or debunk encouragement. I am guilty of this, and it hasn’t made me any better off.

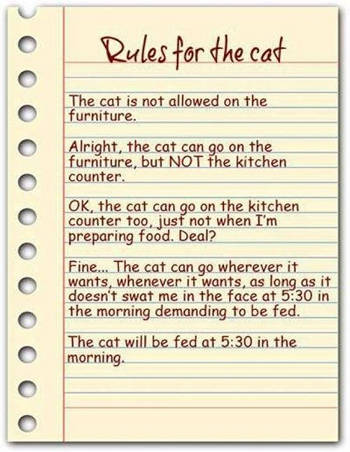

On a more general level, though, perhaps it would also help to read regularly. When you finish a draft of a story or chapter or scene or sentence, read it aloud. I sometimes do this to help catch mistakes, repetition, awkward structures, etc., but the actual reading element has always been secondary. In retrospect, I think those are missed opportunities to practice performance-grade reading, rather than mumbling through the lines under my breath. Cats make a pretty good trial audience, in that they let you practice coping with that sense that you’re reading to someone who has no interest in listening to you.

I survived, by the way, as have most reading-shy writers before me. If you’re curious, I read a version of “Confidentiality” cut essentially in half to fit the time limit. I don’t envy the people at Reader’s Digest, but that’s another matter entirely.

I survived, by the way, as have most reading-shy writers before me. If you’re curious, I read a version of “Confidentiality” cut essentially in half to fit the time limit. I don’t envy the people at Reader’s Digest, but that’s another matter entirely.

Bottom line is, reading for an audience is hard, and anyone who says it’s not is either lying or a sociopath (or maybe both). But it’s also a good thing. During the Q&A after I finished, I got very positive feedback, signs that people had enjoyed my work. I was even able to not-too-tackily-I-hope point them to this blog. Have I suddenly developed a huge, thriving fanclub? No. But I connected with people, at least for fifteen minutes, and maybe that will give me the opportunity to connect with them again. Plus I didn’t vomit even once.

All this is to say, I try to be skeptical, but I know I’m not immune to superstition. And when I’m not harnessing my productivity, instead watching TV shows online, I have a special weakness for

All this is to say, I try to be skeptical, but I know I’m not immune to superstition. And when I’m not harnessing my productivity, instead watching TV shows online, I have a special weakness for  It’s a funny idea. We use that term—grown up—as if it’s a defined threshold, when of course it’s not. I think to many people, growing up means growing out. Maybe you grow out of your childhood bedroom, your childhood home, your hometown, your high school friends, your lifestyle—whatever form it takes, that snake-like shedding of skin seems to characterize grown-up-hood. But some things we never grow out of. Or perhaps that’s not the problem—we grow out of things just fine. It’s the other stuff we have to contend with.

It’s a funny idea. We use that term—grown up—as if it’s a defined threshold, when of course it’s not. I think to many people, growing up means growing out. Maybe you grow out of your childhood bedroom, your childhood home, your hometown, your high school friends, your lifestyle—whatever form it takes, that snake-like shedding of skin seems to characterize grown-up-hood. But some things we never grow out of. Or perhaps that’s not the problem—we grow out of things just fine. It’s the other stuff we have to contend with. I have two cats. This list sums up our relationship, because my approach to cats is like my approach to short jokes: what happens will happen—just don’t fight it. What this means for my approach to writing, in turn, is that if a cat chooses to lie down across my arms while I’m typing, I’ll keep going, because hey, if I can’t reach that top row, I’ll just spell out the numbers, hold off on the em dashes, and make sure no one gets excited enough to need an exclamation mark. And if a

I have two cats. This list sums up our relationship, because my approach to cats is like my approach to short jokes: what happens will happen—just don’t fight it. What this means for my approach to writing, in turn, is that if a cat chooses to lie down across my arms while I’m typing, I’ll keep going, because hey, if I can’t reach that top row, I’ll just spell out the numbers, hold off on the em dashes, and make sure no one gets excited enough to need an exclamation mark. And if a