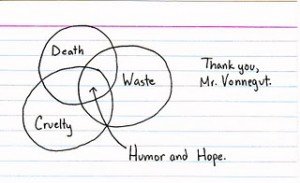

Lately I have had Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night on the brain. I’ve talked about Festinger and Carlsmith’s tedium, Milgram’s volts … but not much about the book itself. So let’s move on to Das Reich der Zwei: the nation of two.

Some background, and my apologies if I mess up any details—I’m away from home at the moment, without my copy of the book, but I wanted to write this now:

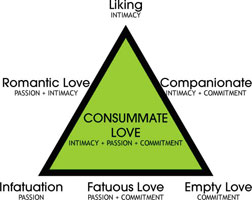

Howard W. Campbell Jr. is born in the United States but spends most of his early life in Germany. He marries a German woman, Helga Noth, daughter of a police chief. He is a playwright; she, the lead actress in many productions. Together, they make up what he calls das Reich der Zwei. Together, they occupy a space uniquely theirs, sovereign and autonomous and separate from the rest of the world. Together, even as Germany descends into war and Howard becomes involved in the transmission of coded messages to US forces, they exist in a solitary, untouchable peace.

Observe a special sort of couple for any amount of time, and das Reich der Zwei becomes apparent. Between them, a culture will have developed. In a chaotic, dissonant world, they will have their own resonance. Their own lexicon and idioms and speech patterns, their own legends and mythologies, their own traditions and celebrations and solemn observances of tragedy. Try to make a home in their Reich der Zwei, and you will never move beyond resident alien status, will never be able to fully assimilate.

Such is the nature of the nation of two.

Helga meets an untimely end. Das Reich der Zwei crumbles. Howard is left at the mercy of other nations—Germany, the United States, Israel—snapping like hungry wolves for meat fresh from his bones.

Trying to emigrate from the nation of two, though, is as successful as trying to immigrate to it. That culture becomes part of you, and although you may adopt different customs, come to appreciate foreign cuisine and find the new language coming more and more easily, your heart will always belong to your nation of two.

Somehow, knowing that ein Reich like yours could exist makes it all the more difficult to survive in the bigger, noisier, messier world.

This is why, before the novel’s outset, Vonnegut says, “And yet another moral occurs to me now: Make love when you can. It’s good for you.”