I don’t have a TV. Not because I’m one of those people who’s harnessed her productivity by rejecting television; I just haven’t plunked down the money for one yet, and at this point, when I’m angling to move in a few months, it seems better to hold off. Thanks to the internet, though, I don’t have to use that lack of TV as an opportunity to do work. You’ll see.

B. F. Skinner easily demonstrated superstitious behavior in pigeons, but we’re mistaken if we think having something bigger than a birdbrain puts us above that. We all have our superstitions—some that we acknowledge, some that we defend, some that may in fact prove accurate. Take the number seventeen. Look for it. Fill up the gas tank for $32.17? Hit. $11.72 for lunch? Hit. Finally buy a TV for $280.34 (2+8+0+3+4=17)? Hit. I live in Ypsilanti, Michigan: Y-P-S-I-L-A-N-T-I-M-I-C-H-I-G-A-N, seventeen letters. I have a class in the development of psychology called History and Systems of Psychology: H-I-S-T-O-R-Y-A-N-D-S-Y-S-T-E-M-S, seventeen. With A=1, B=2, C=3, etc., the letters of my license plate add up to 40, and the numbers add up to 23, and 40-23=17. Today is the twentieth of March, the third month: 20-3=17. I’m 5’3.5″, 4″ on my driver’s license: 5+3+5+4= … you get the idea.

This might seem silly, and it is, because I’m sitting at my desk with a cat sprawled across my arms, trying to come up with examples in a matter of minutes. I did pick the number first, though, and it would work just as well with 16 or 18 or, say, 13. Once you decide something is significant, you become biased, seeing only the confirmations. I didn’t note, for instance, that although 20-3=17, there’s no reason to subtract, except that 20+3, 20×3, 20+3+2013, etc., do not =17. For every hit, there are a multitude of misses … but the misses aren’t interesting, so we tend to ignore them.

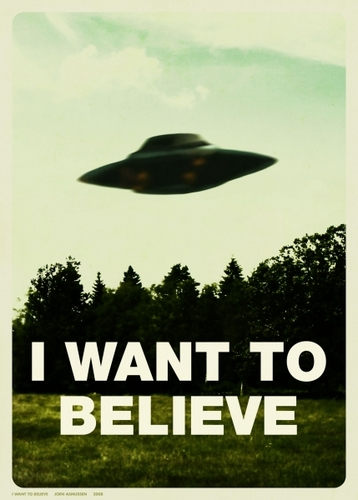

All this is to say, I try to be skeptical, but I know I’m not immune to superstition. And when I’m not harnessing my productivity, instead watching TV shows online, I have a special weakness for shows about “real” ghosts. It isn’t that I believe in ghosts; to be honest, I don’t know what it is that appeals to me. Author Rebecca Makkai suggests that there’s something hopeful in the ghost story, which at first struck me as odd—when I recall seeing The Sixth Sense, I don’t think of it as an inspirational, uplifting movie.

All this is to say, I try to be skeptical, but I know I’m not immune to superstition. And when I’m not harnessing my productivity, instead watching TV shows online, I have a special weakness for shows about “real” ghosts. It isn’t that I believe in ghosts; to be honest, I don’t know what it is that appeals to me. Author Rebecca Makkai suggests that there’s something hopeful in the ghost story, which at first struck me as odd—when I recall seeing The Sixth Sense, I don’t think of it as an inspirational, uplifting movie.

But maybe she’s right. When we write about a ghost, the implication is that the human (or dog, or whatever) story doesn’t end at death. This can be good or bad, depending on how that story goes, but so much of the fear of death boils down to a fear of the unknown, and in a ghost story, what comes next becomes a little more knowable. And knowledge, as they say, is power.

I’m fleshing out the loose concept for what I can best describe as a ghost story without a ghost, and it forces me to ask what a ghost story looks like. Is ghostliness a state of being—in which case my ghostless story is by no measure a ghost story—or something more complex? And if ghostliness isn’t defined by actual status as ghost, what is it?

If personhood is the union of spirit and body, Lauren Groff suggests, ghosts are spirit without body. Given this definition, I think my story could qualify. It’s sort of the idea of being nobody—no body—and being involved in a world without being a physical entity in it.

Maybe that’s what the ghost of literature (though perhaps not Ghost Hunters International) is: the absent presence, the embodiment of the disembodied. Pick an existential oxymoron, and there you have it.

A ghostless ghost story, then, might not be such a stretch.