When I was young, I played a computer game called Logical Journey of the Zoombinis. I don’t remember much about it, except that the goal was to successfully navigate bands of Zoombinis from one side of a map to another, solving logic puzzles to avoid perils along the way.

When I was young, I played a computer game called Logical Journey of the Zoombinis. I don’t remember much about it, except that the goal was to successfully navigate bands of Zoombinis from one side of a map to another, solving logic puzzles to avoid perils along the way.

One of those puzzles requires you to suss out the pizza preferences of a couple troll-like creatures. You offer them different toppings in combinations until they’re pleased. Until they’re satisfied, they’ll respond to your offers with either, “More toppings!” or, “Something on that I don’t like,” flinging the pizza away in rejection.

Screw up too many times, and your little Zoombini server gets booted out of your party.

In related news, I recently read Sideways, by Rex Pickett.

I recently read Sideways and, on several occasions I found myself with an urge to fling the book away and declare, “Something in that I don’t like!” That something, I realized quickly, was the characters.

I’ve read plenty of books with central characters I disliked, though, and I wasn’t always struck by the urge to fling them away … which makes me wonder what, exactly, that difference is.

There are all sorts of reasons I dislike people, some of them more legitimate than others, so perhaps that’s part of it—different characters are unlikable for different reasons. I enjoy a charming sociopath, for instance even if the sociopathy outweighs the charm and I don’t actually like the character. Perhaps the most striking example from my recent reads is Horns, by Joe Hill. There are a few characters whose heads we get to inhabit, and none of them are particularly likable—one of them, in fact, becomes something akin to the devil. Yet I enjoyed the book, to the point that I’ve recommended it to several friends.

Those Sideways characters, though. They have inspired me to warn several friends away from it (or else assure people who meant to read it before watching the film adaptation that really, they didn’t miss anything).

The New York Times recently published a pair of short essays by Moshin Hamid and Zoë Heller on the matter of unlikable characters. Hamid observed:

I’ll confess—I read fiction to fall in love. That’s what’s kept me hooked all these years. Often, that love was for a character: in a presexual-crush way for Fern in “Charlotte’s Web”; in a best-buddies way for the heroes of “Astérix & Obélix”; in a sighing, “I wish there were more of her in this book” way for Jessica in “Dune” or Arwen in “The Lord of the Rings.”

Then, though, he goes on to note that, “In fiction, as in my nonreading life, someone didn’t necessarily have to be likable to be lovable.”

It’s an important distinction, likable vs. lovable, and one that—in different ways—we’re all familiar with. It’s like that line that gets floated around in different fonts, superimposed over different images: At some point you have to realize that some people can stay in your heart but not in your life (or some variation thereof). We’ve all been there, loving something that was not, by objective measures, good—a person, a behavior, a life state, whatever. But goodness—likability—isn’t the primary criterion we use sometimes.

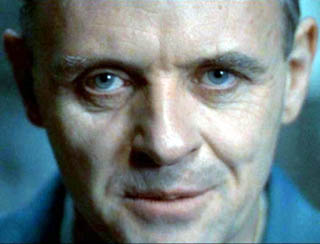

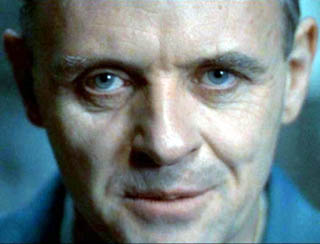

Few would argue in defense of Dr. Lecter’s dietary preferences. And yet we love him. Or, at least, I do.

Few would argue in defense of Dr. Lecter’s dietary preferences. And yet we love him. Or, at least, I do.

So what’s a writer to do with this? Likable might not be good enough to be lovable, and unlikable still needs to leave room for lovable.

The short answer is, I’m not sure. Writing always has an element of trial and error, the same as in real life. I can list off characteristics of people I love (in a broad sense) and although that’s a start, it doesn’t mean I’ll love everyone who meets those criteria—or that I won’t love anyone who doesn’t. I have to actually interact with those people. Still, here are some points I would put out:

- a lovable character has agency (we can pity a victim, but pity isn’t love)

- a lovable character wants something (otherwise it’s just a lazy afternoon with an echoing, “I dunno, what do you want to do?”)

- a lovable character makes decisions (we, as readers, are along for the story’s ride; we need more from a character)

- a lovable character faces a genuine but potentially surmountable obstacle (if it’s all smooth sailing, or if there’s no reason to hope, we have nothing to wonder about, and wonder is a key component of love)

That’s an imperfect list, of course. (You’ll notice that much of it has as much to do with story as with character. Separating the two seems, in ways, a pointless exercise, because one without the other loses either its context or its importance. But that’s another matter entirely.) If you have any to add, leave me a comment.

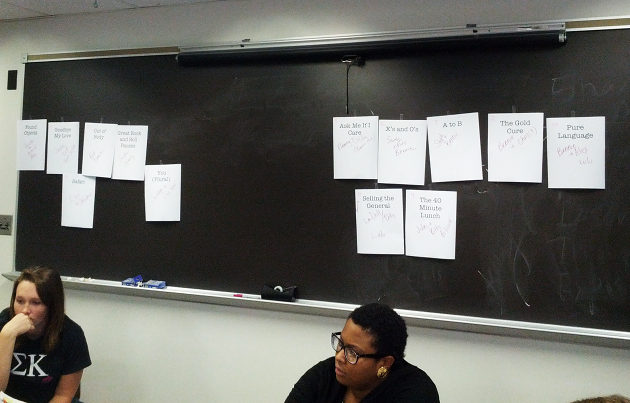

This week marks the more-or-less midpoint of my linked stories course with Cathy Day, and the last of our reading-focused classes. (Up next: workshops.) We

This week marks the more-or-less midpoint of my linked stories course with Cathy Day, and the last of our reading-focused classes. (Up next: workshops.) We

When I was young, I played a computer game called

When I was young, I played a computer game called  Few would argue in defense of Dr. Lecter’s dietary preferences. And yet we love him. Or, at least, I do.

Few would argue in defense of Dr. Lecter’s dietary preferences. And yet we love him. Or, at least, I do.