Dissonance does funny things to people.

In 1959, Festinger and Carlsmith set people at a tedious, seemingly pointless task for an hour. After the task was finished, some of the participants were sent on their way; the others were asked to do a favor: go to the waiting room and tell the next “participants” (actors) that the task was interesting. Half these people were offered $20 (~$150 today), and the other half were offered $1 (~$7.50). When asked to rate their own response to the task, participants given $1 tended to call it more interesting than those given $20.

Here’s the explanation posed by Festinger and Carlsmith.

The task was boring. One would be hard-pressed to see it otherwise. But the participants told others that it wasn’t. The ones given $20 could use that money as solid justification, could tell themselves, “I said that because hey—$20!” The others, though, had only a dollar’s excuse. So, they reasoned, since the incentive wasn’t that great, there must’ve been more than that behind their claim that the task was interesting—for instance, maybe the task actually was interesting. If it hadn’t been, after all, why would they have said so for just a dollar?

We want to align things in our minds. When a few dissonant notes are struck, we want them to resolve into a major chord. Sometimes that means changing our circumstances—e.g., if I start reading a book and dislike it, I can stop. Other times, though, that means changing our perspectives.

I recently read Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night. The introduction begins …

This is the only story of mine whose moral I know. I don’t think it’s a marvelous moral; I simply happen to know what it is: We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.

… and concludes …

There’s another clear moral to this tale, now that I think about it: When you’re dead you’re dead.

And yet another moral occurs to me now: Make love when you can. It’s good for you.

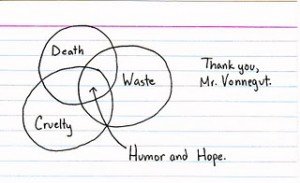

Vonnegut is known for his irreverence and the ubiquitous so it goes, but also—maybe most—for his dark humor. Jessica Hagy expresses it well:

Vonnegut, I would suggest, thrives on dissonance.

[to be continued]