I knew a man who had a complicated relationship with his father. I should give him a pseudonym—we haven’t talked in years and I don’t know if he would appreciate me writing about him without asking first—but what could I substitute to make it hit the same way when I tell you that his pastor father named him Adam?

Adam’s father died this summer. I learned the way I learn most things these days: online, by accident. I started to type something into the address bar, and my browser autocompleted to Adam’s website. He must’ve let it expire; the URL now belongs to a Chinese patent agency. I googled his name and found the obituary on the second page.

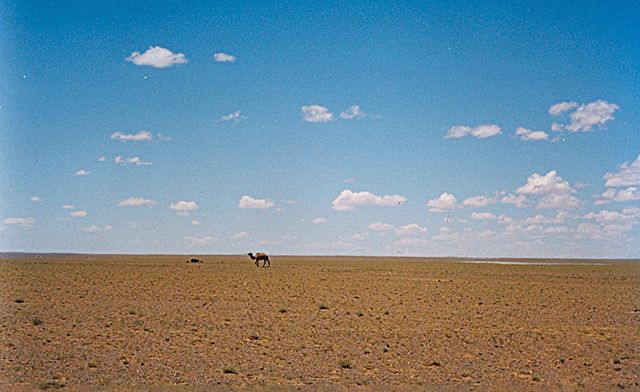

I never met Adam’s father, but I disliked most of what I knew about him. The complex trauma of that family cut deep, and I could see it in Adam and the stories he told me—stories that gradually let me feel like a fly-on-the-wall observer in a sepia-toned flashback, an invisible member of the household in retrospect. One winter, we drove twelve hours to his childhood home, now abandoned. We slept in the car, huddled against the New England cold. The next day, we climbed the nearby mountain so he could recapture the view from his youth, but the fog was dense at the top, so thick I might have lost sight of him if I had wandered too far.

Grief is a tricky thing, rogue-like in its ability to catch you off guard with a knife to your throat and a whispered directive to act normal and follow its instructions. Sometimes it keeps things simple and drives the blade between your ribs—or, simpler still, lifts your wallet and makes its escape before you notice anything missing. I was the one who cut Adam out of my life, but self-inflicted pain still hurts. Last I heard, he and his father weren’t speaking, a point of tension among his siblings. I don’t know if I hope they were able to reconcile.

Edith Wharton, late in her writing career, wrote:

Edith Wharton, late in her writing career, wrote: