This is the second of two posts (first one here) from my linked stories class. Now, we’re going to talk about Cambria, PowerPoint, and our second class activity.

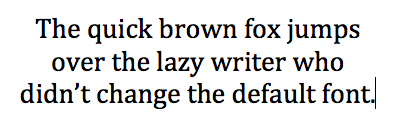

So let’s backtrack for a moment to early in the class period. We discussed formatting—for our upcoming projects and for fiction in general. Prof. Day advised us not to use Cambria, which is the default font for Microsoft Word. (I’d take it one step further and say don’t use Word, but that’s another matter.) Many of Word’s settings are better changed because, as she put it, “You’re the boss of Word!”

So let’s backtrack for a moment to early in the class period. We discussed formatting—for our upcoming projects and for fiction in general. Prof. Day advised us not to use Cambria, which is the default font for Microsoft Word. (I’d take it one step further and say don’t use Word, but that’s another matter.) Many of Word’s settings are better changed because, as she put it, “You’re the boss of Word!”

I don’t know about Jennifer Egan’s relationship with Word, but I can tell you right now that she is the boss of PowerPoint.

Our Activities, Part II: Translating PowerPoint to Normal Story

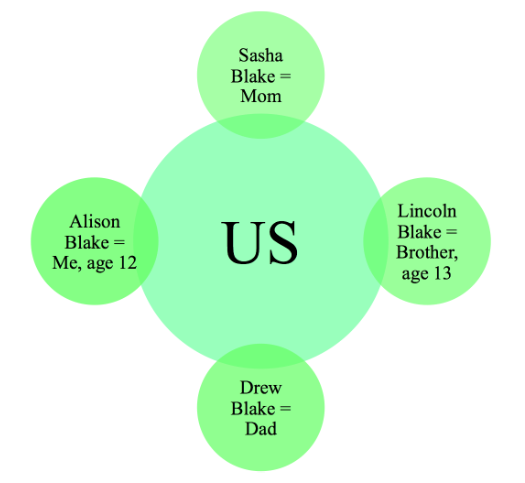

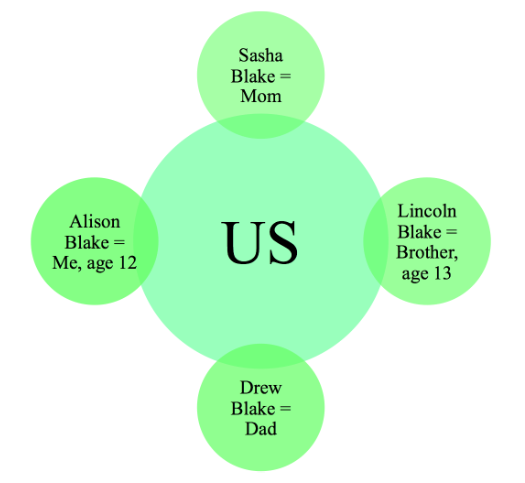

As I mentioned last time, Chapter 12 of Goon Squad, “Great Rock and Roll Pauses,” is told entirely in PowerPoint slides. The fictional slidemaker, 12-year-old Alison, reveals a portion of her family life, including her brother’s obsession with the pauses in songs.

It’s hard to discuss how this piece works without having read it, so if you didn’t click the link earlier, go now. It’s a quick—and unique—read. Of it, Egan says,

Goon Squad is a book about time, composed of 13 discrete stories separated by gaps. And PowerPoint (or any slideshow, it doesn’t have to be Microsoft) is a genre composed of discrete moments separated by gaps. As a genre, it echoes the structure I was already working with in Goon Squad, and its corporate coldness allowed me to be overtly sentimental in ways I probably wouldn’t have allowed myself to in conventional fiction.

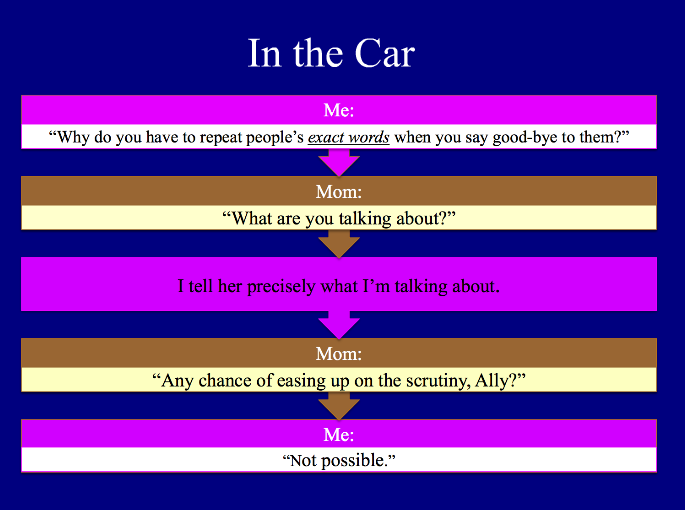

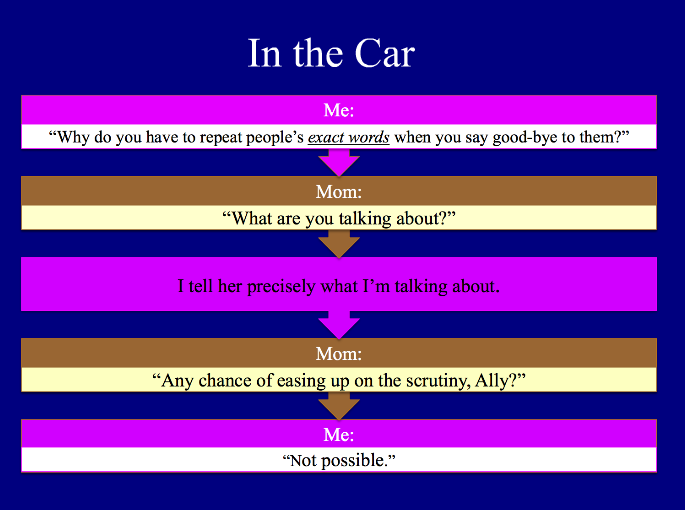

Our task, having read this chapter, was to take a ten-slide portion of it and translate it into “conventional fiction.” Some slides make it pretty easy by being single linear exchanges:

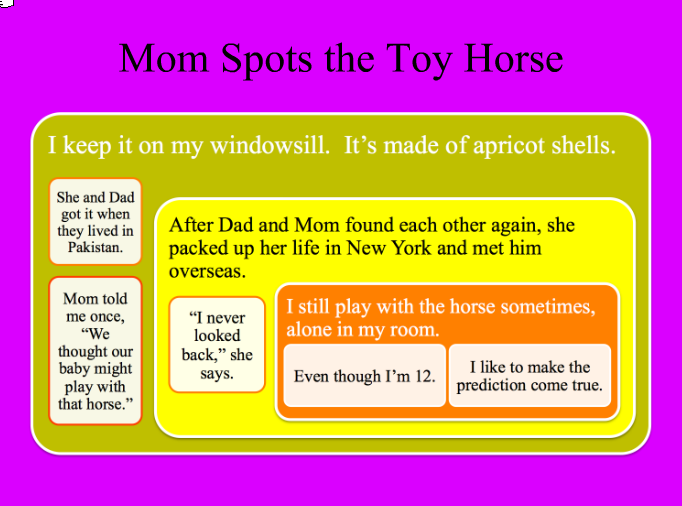

All slides © Jennifer Egan

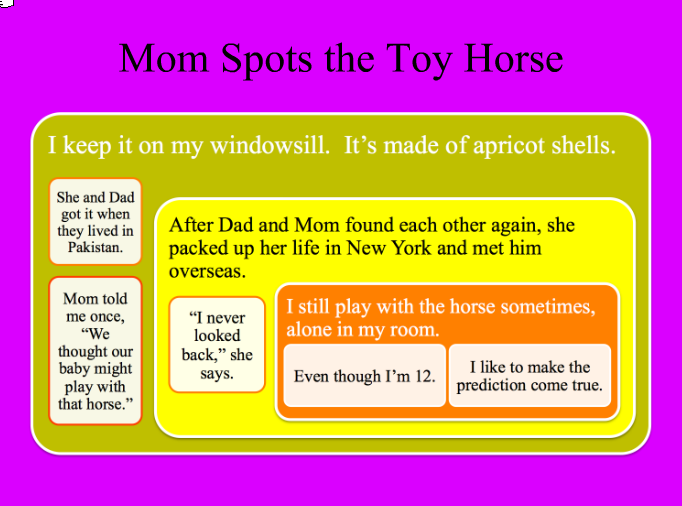

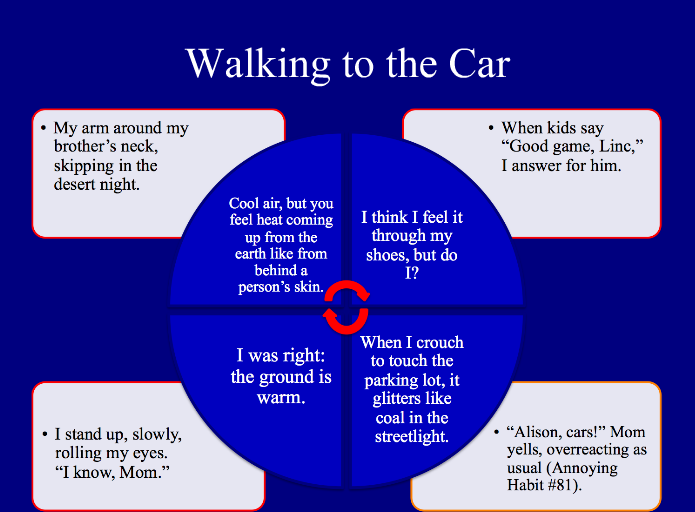

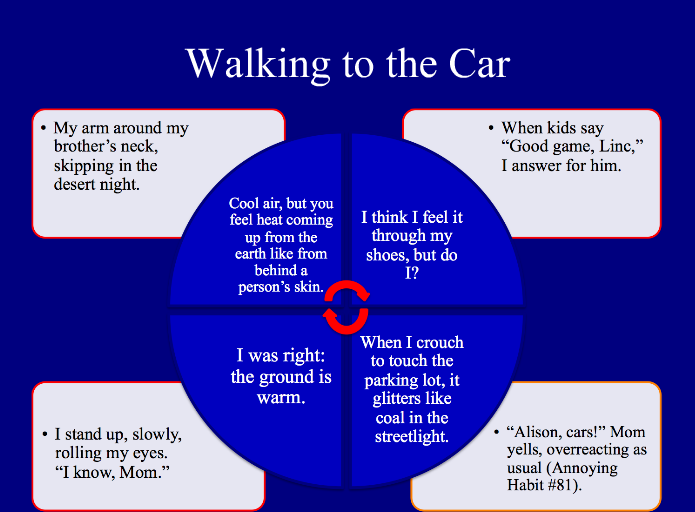

Some make it more difficult by being nonlinear in form and all over the place in time:

Some just can’t be captured the same way in “normal story”:

And some are simple statements of fact:

Although we grappled with the nonlinear ones, these last, factual ones seemed to give us the most difficulty—we didn’t feel free, as Prof. Day put it, to “transform the data into good fiction” and so tried to do a too-literal translation. (As any foreign language study will show you, a literal translation of anything complex is rarely successful.) It’s a common problem even when we’re not translating from PowerPoint, though. How do we convey information without just resigning to the dreaded “info dump”? What do we do with that green-circle slide, other than turn it into a list of dramatis personae?

For starters, recognize that we can work it in over time. Take the fifth slide:

My translation went like this:

We’re walking to the car, skipping in the desert night. My arm is around my brother’s neck, and when kids say, “Good game, Linc,” I answer for him.

It’s cool air, but you feel heat coming up from the earth like from behind a person’s skin. I think I feel it through my shoes, but do I? When I crouch to touch the parking lot, it glitters like coal in the streetlight. I was right: the ground is warm.

“Alison, cars!” Mom yells, overreacting as usual (Annoying Habit #81).

I stand up, slowly, rolling my eyes. “I know, Mom.”

So, for instance, I might have referred to the junior high baseball league to approximate Lincoln’s age, and called him Alison’s older brother. I might have remarked on the father’s absence from the game to show that he’s also an important character, even if he isn’t in this scene.

It’s a good exercise, considering how you might translate these things. If you’re following along but haven’t been keeping up on the activities, try this one. Give yourself the same ten-page assignment and see what you come up with. (Leave it for me in the comments, even—I’m curious.)

What’s next?

For us, we’ll be kicking off workshops soon, looking at material for our final projects. For you, you can kick off a workshop as well. Find a writing group near you, or start one, or seek out an online community. Share what you’ve learned by following our class, and exchange stories. In other words, make links.

I am linking. Are you?

Specifically, Asheville, North Carolina.

Specifically, Asheville, North Carolina. Writers are a crazy lot. It’s just something we assume, and

Writers are a crazy lot. It’s just something we assume, and  So let’s backtrack for a moment to early in the class period. We discussed formatting—for our upcoming projects and for fiction in general. Prof. Day advised us not to use Cambria, which is the default font for Microsoft Word. (I’d take it one step further and say

So let’s backtrack for a moment to early in the class period. We discussed formatting—for our upcoming projects and for fiction in general. Prof. Day advised us not to use Cambria, which is the default font for Microsoft Word. (I’d take it one step further and say

This week marks the more-or-less midpoint of my linked stories course with Cathy Day, and the last of our reading-focused classes. (Up next: workshops.) We

This week marks the more-or-less midpoint of my linked stories course with Cathy Day, and the last of our reading-focused classes. (Up next: workshops.) We