Last time, I talked/gushed about Literature and Latte’s application Scrivener. Not so long ago, I decided to try out another program of theirs, Scapple.

The basic premise: Scapple lets you put down ideas, make connections between them, shift them around, and more. Literature and Latte describes it as a “freeform text editor” and explains,

Scapple doesn’t force you to make connections, and it doesn’t expect you to start out with one central idea off of which everything else is branched. There’s no built-in hierarchy at all, in fact—in Scapple, every note is equal, so you can connect them however you like.

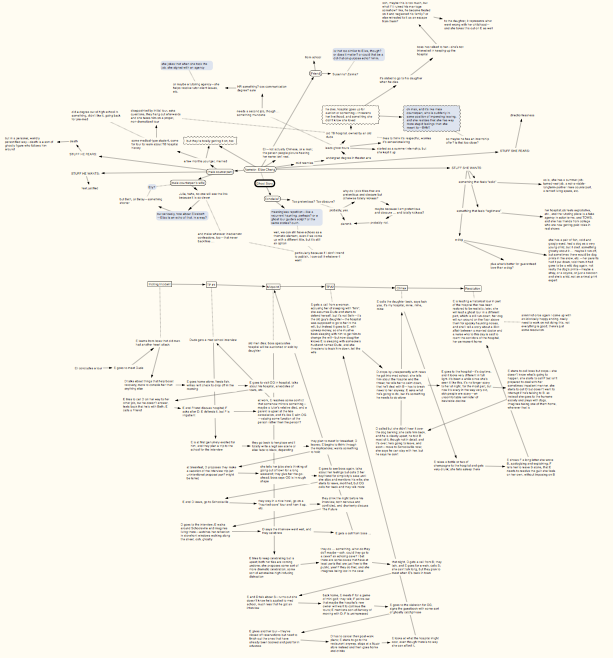

I tested it out in the early stages of prep work for the novel I’m working on (the ghostless ghost story I mentioned a few months ago). Here’s the end result, zoomed out to show the whole thing:

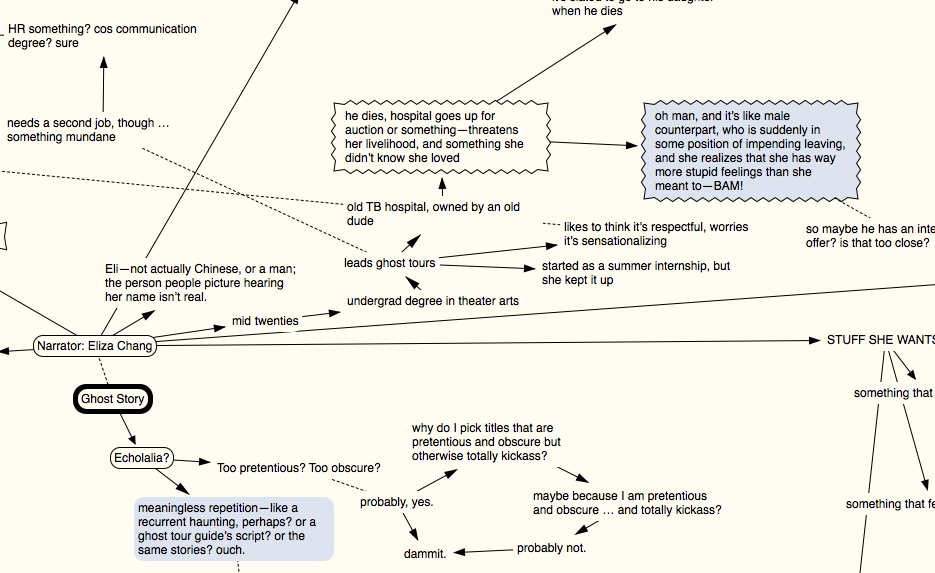

And here’s a smaller section that’s actually legible:

About five years ago, I went through a phase of freeform brainstorming a little like this. I had a big pad of newsprint paper (something like this) and a pack of these multi-colored markers, and I’d sit on my dorm room floor, writing down different questions and answers about the project in different colors and orientations. I fell out of the habit, but working with Scapple reminds me a bit of that. The primary difference, of course, is that my marker notes couldn’t be rearranged, connected and disconnected and changed to a different color.

So, Scapple. What can I say about Scapple? I haven’t used it much beyond what’s above, so I can’t speak to/gush about it to the same extent I can Scrivener. I wouldn’t say I’ve fallen in love with it yet, but it was certainly a useful process to map out my novel as the concept developed (I sometimes think of this prep work as a sort of skeletal first draft) and Scapple provided a flexible way to do that.

Here’s an analogy. One of the more difficult things about taking lecture notes can be connecting and ordering them in a way that will make most sense later. Is this mention of a study with conflicting results going to be a passing mention that should be another subpoint, or are we going to explore it in detail in its own right? And if it becomes its own point, should the first study’s authors’ rebuttal be noted in the margin back up there, or should it be included with this second study?

This is a place where taking notes on a computer can simplify the process, because if I discover as the lecture goes on that something would do better indented farther, or moved back out, or expanded on, or cut and pasted somewhere else, it’s an easy fix. The flexibility of Scapple works in a similar way, allowing easy expanding and moving and reclassifying. Different people, obviously, prepare for novels differently, but my initial work is sloppy—to an outsider, it might look like I write a bunch of unrelated things on index cards, shuffle them up, and pick five of them to give me a randomly generated premise. Scapple supports this, letting me toss tidbits anywhere on the screen and, once I begin to see connections, shape those tidbits into something that becomes more and more cohesive.

Scapple has been a fun exercise. It hasn’t been as revolutionary as Scrivener, but I have been able to put it to use beyond frivolous experimentation. Should you buy it instead of groceries? No, probably not. But if you’ve got $15 to spare, Scapple is a better investment than many alternatives.