This week marks the more-or-less midpoint of my linked stories course with Cathy Day, and the last of our reading-focused classes. (Up next: workshops.) We started the semester with the least linked stories, Short Cuts, and worked our way toward more and more tightly linked pieces, finally reaching today’s book, A Visit from the Goon Squad, whose second-edition cover identifies it as a novel.

This week marks the more-or-less midpoint of my linked stories course with Cathy Day, and the last of our reading-focused classes. (Up next: workshops.) We started the semester with the least linked stories, Short Cuts, and worked our way toward more and more tightly linked pieces, finally reaching today’s book, A Visit from the Goon Squad, whose second-edition cover identifies it as a novel.

To my regular readers: This will be a stylistic departure. I’m preparing this post as the first of two to be shared on our class blog, where you can follow along with us.

To my new readers: Hi. My name is Alice, and I’m here to talk to you about …

What We Read: A Visit from the Goon Squad

A Visit from the Goon Squad is the result of Jennifer Egan‘s challenge to herself to write a book with chapters “as different from each other as possible, yet still adding up to one story.” (source) After an interview with Egan, Emma Brockes observes,

The idea for Goon Squad came to her after her reading group got stuck into Proust. It took them about seven years to plough through In Search of Lost Time, during which she became obsessed with how to represent entire lifespans, non-sequentially and in the way people actually experience them, that is as a constant negotiation between reflection and anticipation.

The twelfth chapter of Goon Squad is written as 12-year-old Alison’s autobiographical slideshow, complete with sound effects (if read online, as was Egan’s initial expectation). Another story is told in second-person. Still another is a news article. Different narrators, different protagonists from one chapter to the next, different time periods over forty-some years—and now identified as a novel?

Our Activity: Reorganizing Goon Squad

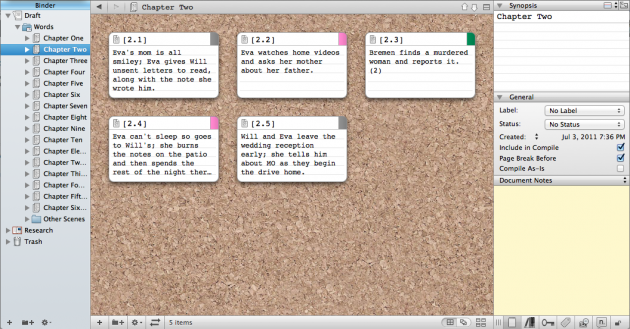

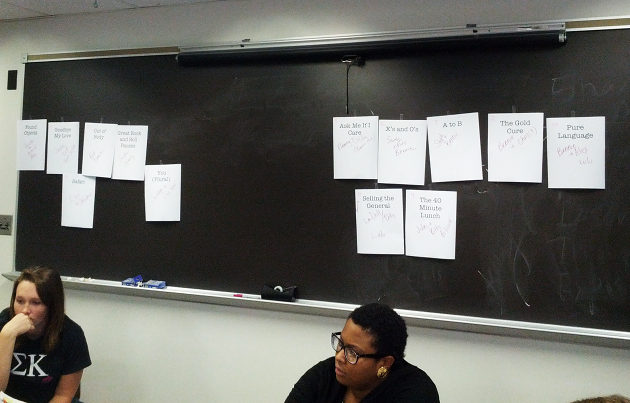

Because of the delightfully mixed-up nature of this book, an obvious exercise is to experiment with different ways of ordering the chapters. What would happen, for instance, if we extracted all the chapters that prominently feature Bennie? Or Rob’s death? What if we put them in chronological order as best we can?

Pictured: Kate Gutheil and Ashley Mack-Jackson with chapters sorted into character-based arrangements

(A past, particularly ambitious reader had done something like this already. Tyler Petty went through the book and outlined the timelines for twelve different characters.)

As we reflected on this task—the difficulties in mapping out an exact timeline, the costs of every rearrangement—someone declared that Egan had already put it in the best order. Prof. Day said, “I know.”

Takeaways

The order of chapters/sections/stories in a book goes a long way in determining how it’s read. Chronological Goon Squad, for instance, doesn’t have the same emotional effect, because information gets doled out differently. Good Squad organized by major character loses the interwoven, interdependent feel.

That doesn’t mean, of course, that a more conventional structure is always bad. It just means that organization should never be taken for granted, that we shouldn’t default to one form because that’s how it’s usually done (or for the sole purpose of being different) without thinking about how it will serve the book we’re writing. We need to take time for these questions, to make these decisions deliberately, open to the possibility that the first way we try it might not be the best. (We also have to recognize that there are Tyler Pettys out there, so if we’re going to play with chronology, we better make sure we double check our math.)

What I Learned

I’ve experimented some with chronological deviation in novels and written chronologically-ambiguous short stories, mosaics of scenes whose temporal relations aren’t explicit but are clearly not chronological. But I haven’t written—or contemplated in-depth—something with the scope of Egan’s book. The questions and considerations presented by a project like Goon Squad are fascinating (if somewhat daunting). The most important thing, though, was that reminder that no decision should be taken for granted in writing, and that there are questions worth asking that I might not think of at first.

What’s next?

In a few days, I’ll share the second half of our class activities, which focused specifically on that twelfth chapter.